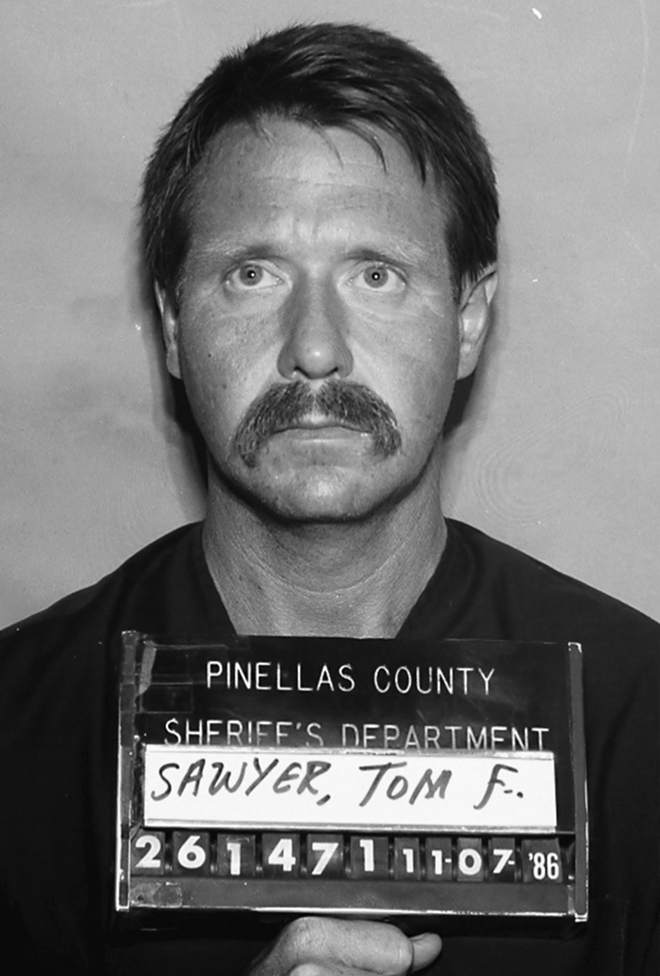

Tom Sawyer sat in the front row of Courtroom 2 at the Pinellas County Justice Center on 49th Street. Flanked by close friends, including his former lawyer, he watched as a bailiff led Stephen Lamont — scraggly, cuffed and clad in navy blue inmate scrubs — to stand before the judge. Judge Michael Andrews read Lamont’s guilty plea in the 1986 murder of Janet Staschak, then he read his sentence: life with a possibility of parole in 25 years.

He asked Lamont if he understood what was happening, and still wanted to go through with it.

Lamont hesitated for a second.

“Yes,” he replied.

As a bailiff took Lamont away, Sawyer briefly thrust his fists into the air.

Finally, he was free.

For the first time in nearly three decades he wouldn’t be afraid to answer his door.

“I lived in fear any day that anybody came and knocked on the door I might be arrested and brought back to Florida,” said Sawyer after the hearing last month.

That’s because Sawyer, who now lives in Illinois, had been the prime suspect in Staschak’s death for years although he’d been released in 1988 after a judge threw out his confession.

He had been pressured into falsely confessing to the crime in the days following her death, and faced prison — possibly even the death penalty. But last year, when Clearwater police ran DNA from the crime scene through a national database, as they routinely do in cold cases, they came up with a match in Lamont, who was living in Alabama.

For Joseph Donahey, who served as Sawyer’s attorney and is now a retired judge, the case is a clear argument against the death penalty.

“I opposed the death penalty when I was on the bench,” Donahey said. “I oppose the death penalty for the very reason that people in the system are fallible, that we make mistakes and once we have executed somebody we cannot correct it.”

He said the case calls into question a criminal justice issue that doesn’t get as much ink as capital punishment: the techniques police use when interrogating suspects, which can include blatantly lying to suspects in order to obtain a confession.

“Interrogation techniques that are taught in police academies across the country, and [which] the Supreme Court has approved [include] misrepresenting facts to the person you’re interrogating, lying to them, embellishing the truth,” he said. “So those techniques are taught, and they’re trained to do that. If they carry that to its full extent, they may very well coerce a confession.”

And that’s how Sawyer got roped into a grisly murder case nearly 29 years ago.

Sawyer and Staschak were neighbors. Their adjacent two-story apartments in Clearwater shared a small concrete patio. She died from strangulation sometime between November 1 and 3, 1986; she was found naked under a sheet on her waterbed upstairs, her hands and feet bound with twine.

Sawyer was a shy recovering alcoholic in his early 30s with a habit of nervously mopping his brow who worked as a landscaper at a nearby golf course. Staschak was an outgoing 26-year-old cake decorator at a Kash ‘n’ Karry on U.S. 19. Police, investigating the crime scene next door, zeroed in on him. An ardent fan of television crime dramas, Sawyer was all too eager to help the police get their guy.

What he didn’t know was that police had their guy, and it was him.

When he went to the station for questioning after work, hoping to give them details no one else knew, he wound up stuck in a police interrogation room for more than 12 hours, deprived of food, drink and sleep. Detectives Peter Fire and John Dean, employing a standard good cop/bad cop routine, lied to him. They said they had found his hair all over Staschak’s body when all they had was a single hair that matched his, which was found downstairs in her kitchen (possibly tracked in from the patio during the investigation). He had failed a lie detector test; he was nervous.

They told him perhaps he had blacked out during a “dry drunk,” something they said recovering alcoholics experience, and had killed his neighbor out of unrequited lust.

Ultimately, they wore him down. He confessed to Staschak’s murder and rape (the latter of which was proven to have never happened) and recited details of the act that the detectives had fed him during the interrogation.

Sawyer spent about a year in jail awaiting trial while his attorney, Donahey, fought to suppress the confession, which fortunately had been partially recorded. In 1988, Judge Gerard J. O’Brien threw out the confession because of its reliance on polygraph results and leading questions, the lengthy interrogation duration and Sawyer’s forced sleeplessness. Sawyer was released, but as long as Staschak’s murder was a cold case, he stood to get hauled in at any moment if police thought they had found more evidence against him. When police identified Lamont last year, they were able to place him in Clearwater at the time of the murder. He had escaped from an Alabama prison and been arrested in Clearwater under an assumed name around the time Staschak died.

“It’s just really a wonderful thing that they finally got the guy that did this murder and I hope Janet’s family and friends can now have a little peace and have a little comfort,” Sawyer said. “I know it won’t bring Janet back, but at least they know who did it.”

It’s impossible to quantify the number of people who have been coerced into providing false confessions. But even with the advent of DNA analysis in the late 1980s, it’s clear that such instances still occur.

In Tampa Bay, in 2006, Alex Bostick, then a teenager, was accused of — and falsely confessed to — killing his aunt and uncle in Hernando County. Ultimately, DNA pointed to another suspect.

Stetson University law professor Judith Scully said false confessions were a factor in a third of the exonerated cases catalogued by The Innocence Project, a chapter of which she founded at Stetson.

But the numbers are tricky to pinpoint.

“We just don’t know the answer to that question because it’s very difficult to track,” said Steve Drizin, a clinical professor of law at Northwestern Law School. “Then there are also juvenile cases that are cloaked by rules of confidentiality that make it extremely difficult to access those records.”

Databases cataloguing DNA exonerations show false confessions at play in hundreds of cases. But even if such cases are relatively rare, Scully said, even one wrongful conviction is too many.

“You have to think about the severity of the damage that is caused to one individual if they’re wrongfully convicted,” Scully said. “It doesn’t matter if it’s one individual or 10 individuals. The damage is so extreme that’s done to their life, their family’s life, their communities, as well as the trust that they instill in the criminal justice system.”

She said there are segments of the population that are particularly vulnerable to falsely confessing, namely minors and people with compromised intellectual abilities. In Sawyer’s case, his anxiety may have caused him to cave under all the pressure.

“The psychological interrogation tactics that they use can wear down anybody over time,” Drizin said. “The tactics are extremely powerful and extremely effective at getting the guilty to confess, but they also sometimes get the innocent to confess.”

Police officers aren’t intentionally trying to get people to confess to crimes they didn’t commit, of course.

“Sometimes they get bad information from people on the street who identify [a suspect] as being guilty,” Drizin said. “Sometimes they expect someone is guilty because when they bring them in, they’re looking at their body language and believing that these people are being deceptive when in fact they’re just being anxious.”

And, as Scully points out, officers are under immense pressure.

“I think certainly part of the reason that we have as many wrongful incarcerations in the United States as we do is because there is pressure on many police officers to close cases,” Scully said. “And so they find a suspect and they zero in on that particular suspect with tunnel vision and don’t really do a comprehensive investigation of all the potential suspects.”

There’s plenty of room for reform, activists say.

“The entire state of Florida has been rocked by a number of false confessions over the years and very little has happened in the wawy of reform,” said Drizin. “The state is littered with these false confessions and very little has been done throughout the state to try to prevent them.”

One possible fix, he said, would be to require law enforcement to corroborate confessions with other evidence.

Judges could also instruct juries to view confessions with a degree of skepticism, given that the general public is largely unaware that police are allowed to deceive those they interrogate — and even formally trained to do so via the Reid method, a style of questioning that relies on loaded questions and manipulation. An overwhelming majority of law enforcement officers — some 92 percent, according to a 2007 study — tell suspects there’s evidence against them, video or DNA, when there isn’t.

“Anyone who studies policing in the United States understands that deception and trickery are a formal part, an acceptable part, of police practice,” Scully said. “[Police] are taught that part of their interrogation should utilize the good cop-bad cop method of interrogation. These forms of interrogation lead to false confessions. And yet we continue to trust police officers, knowing that they use tactics that in the general population would be looked down upon.”

Law enforcement agencies in Tampa Bay’s major cities have changed the way they question suspects since Sawyer’s misadventure, though not just because of Sawyer.

Clearwater, for example, now records all of its interrogations on audio and video, and limits the length of time they can take, said homicide Sergeant Mike Ogliaruso. Miranda rights have to be read immediately, which didn’t happen in Sawyer’s case.

He admitted detectives do tend to be more aggressive when interviewing people suspected of serious crimes, but officers are not allowed to tell a suspect they have incriminating evidence when they clearly don’t.

“The difficult part is, yes, you do tend to interrogate supects of major cases harder,” he said. “But the policies, of course, have maybe changed... You’re not able to mislead, to soften the evidence, to change the evidence. I don’t think you can make up evidence to solicit a confession. I think that’s a practice that’s phasing out.”

Tampa Police Department spokeswoman Janelle McGregor says that the agency typically records audio and video of suspect interrogations, though in circumstances where a suspect or his or her attorney does not want the interview recorded, that policy could be waived.

Mike Puetz, a spokesman for the St. Peterburg Police Department, said the department doesn’t use misleading interview tactics, and that most interrogations are recorded. As for reform, he said it’s already up to police to demonstrate the integrity of a suspect’s confession. After all, when a suspect confesses, his or her attorney will likely call it into question off the bat, and police know their interrogation is going to be scrutinized.

“It’s always going to be incumbent on the police to show that any admission they obtain is going to be free and voluntary,” he said. “If the judge feels there’s something wrong with the confession, he’s not going to allow the jury to hear the confession at all.”

Drizin said every law enforcement agency in the country should follow suit.

“It creates an objective, complete reliable account of what happened behind the closed doors of an interrogation,” he said.

As for Sawyer, who had flown to Tampa Bay to watch his former neighbor’s killer get locked up, he said he’s no longer angry at the detectives who goaded him into confessing, even though he never got an apology from either of the officers who tried to put him away. (Current Clearwater Police Chief Daniel Slaughter, who was a teenager at the time of Sawyer’s ordeal, has apologized for the ordeal.)

“I forgive them,” Sawyer said.

But he won’t forget, either.

“And I’ve said this before,” he said. “They were ignorant, they were arrogant, they were close-minded and and they were very sloppy in their investigative work. There were people they didn’t interview they should have. They mishandled evidence. They should be ashamed of themselves.”