Ignore the rising rents, housing shortage and Gov. Ron DeSantis’ wild west approach to reopening for just a moment, and think about how gorgeous your hometown is. Thanks in part to the Buccaneers, Lightning, Rays and Rowdies—and not to mention the winter storm ravaging the rest of the U.S this week—eyes have turned towards Tampa Bay as a great place to make a living. And with pride and interest in our neck of the woods peaking, there’s never been a better time to look back at how we got here.

Thankfully, there’s a collection of photos for that. The most famous one was curated and captured by the Burgert Brothers, Al and Jean Evelyn, who led one of old Tampa’s leading commercial photography firms. The brothers were most prolific from the early-1900s to the early-1960s, but the Hillsborough County Public Library Cooperative has nearly 19,000 Burgert stills that date back to the late-1800s.

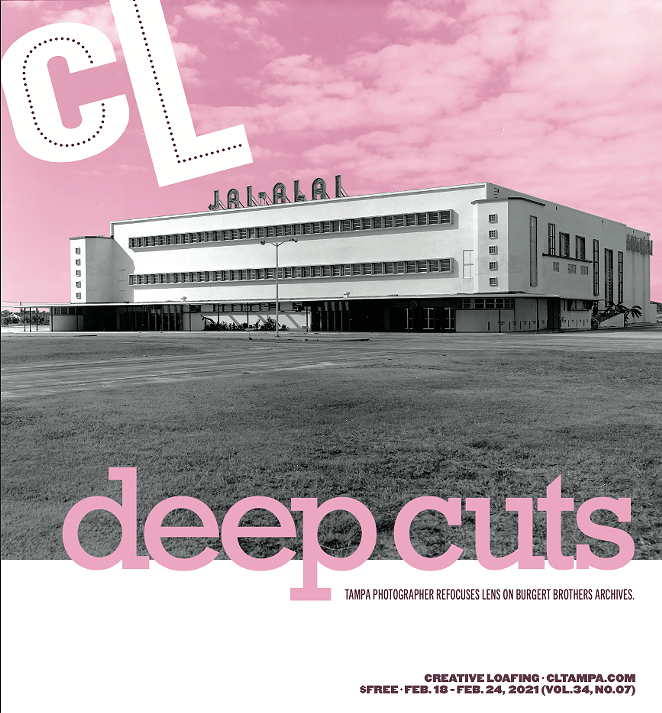

"BURGERT BROTHERS: THEN AND NOW" BY CHIP WEINER

These vintage photos show how much Tampa has changed in the last century

Tampeño photographer Chip Weiner moved here in 1964 and became obsessed with that collection as well as photos from a collection owned by the University of South Florida. So in August, he started to pore over more than 12,000 Burgert shots to begin the research for his new book “Burgert Brothers: Another Look.” The nearly 200-page super-zine finds Weiner (a pre-pandemic contributor to Creative Loafing Tampa Bay) meticulously re-photographing locations in Burgert photos and providing a detailed look into the then-and-now of locales both familiar and obscure.

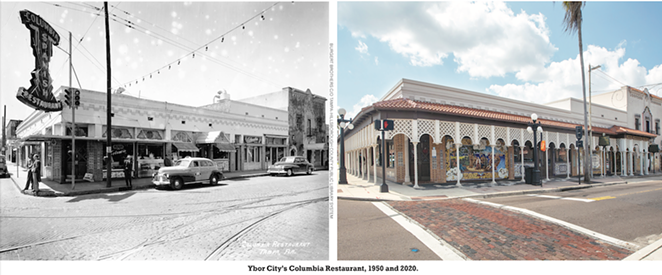

All the greatest hits are there. There’s the Columbia Restaurant in Ybor City (complete with amazing neon signage in the 1950 shot) and the downtown Tampa intersection of Franklin and Polk Streets where in 1960 students from Blake and Middleton high schools, together with NAACP leaders, staged sit-ins at Woolworth. The Cuban, Italian and German clubs are recaptured, along with the iconic intersection of Bayshore Boulevard and Platt Street. There are even handfuls of Hyde Park and Seventh Avenue shots, too.

But some of the book’s real gems come from the less fussed-about parts of the Burgert collection. Like the Coleman’s Super Service station on Floribraska and Florida Avenues, downtown Tampa’s original Goody Goody, Seminole Heights’ Independent Bar, the Gulf Oil station on Bayshore or the Arctic Ice and La Tropical Beer buildings in Ybor. Weiner’s own research even led him to correct some inaccuracies in the original Burgert captions.

“Of the thousands of Burgert portraits that still exist today, you only see about a hundred that are used over and over again, but Chip got some deep cuts,” Rodney Kite-Powell told Creative Loafing Tampa Bay. Kite-Powell is Hillsborough County’s official historian and the Saunders Foundation Curator of History at the Tampa Bay History Center, where he joined the staff in 1994. In short, he is an invaluable fount of local knowledge.

“He dove into that collection… there’s more modern stuff from the ‘50s that you just don’t see, and I hope people will dive in, too. The book belongs out on the coffee table for houseguests and friends to see,” Kite-Powell added. “It should be well-used and never just sitting on the shelf.”

To Kite-Powell—who said that the History Center has picked up books to sell in the gift shop—the amazing thing about the Burgert collection is how many of the shots are still around and available to the public. Newspapers and amateur photographers certainly did their part to capture scenes in a private manner, but the Burgerts were hired contractors and having their photos available to the public in such a large volume is significant. Weiner exhausted every resource—including asking favors of friends—to get his hands on as many hi-res Burgert photos as possible.

“There are some estimates that say that there are anywhere from 50,000-70,000, images, whether they’re negatives or prints. Unfortunately only about 25%, or so, of the collection still exists, but that 25% is just incredible,” Kite-Powell explained. “The public has had access to the collection for so long, and the library was very quick to start putting pictures online and preserve them.”

For Weiner—who spends his non-photography hours as a licensed mental health counselor—honoring the old photographs’ legacy was paramount. The project started out as a personal endeavor, but started to become the book as his pandemic summer, with no face-to-face therapy, went on. He consulted other photographers like Boyzell Hosey, Deputy Editor of Photography at the Tampa Bay Times, and Renato Rampolla for advice. An old medium format film camera and a tilt-shift lens similar to those used by the Burgerts let Weiner indulge in his fascination with the brothers’ process. Being able to spend hours researching newspaper clippings before standing exactly where the Burgerts stood—decades later, but at the same time of day to account for sunlight—and trying to take the same photo was the payoff.

But Weiner stops short of calling himself a historian. In fact, there was a lot of copy—like the lost history of the building that’s home to Ybor City’s Coyote Ugly—Weiner left on the cutting room floor.

![[Morton Williams store and the Exchange National Bank]. Burgert Brothers. Courtesy, Tampa-Hillsborough County Public Library System - Franklin Exchange Building parking garage, 2020. © Chip Weiner](https://media2.cltampa.com/cltampa/imager/u/blog/12436644/screen_shot_2021_02_17_at_5.22.24_pm.602d9862c5115.png?cb=1642532891)

“I wrote just paragraphs and paragraphs,” Weiner told CL. And when it came to his own take on since-demolished landmarks like the Pettaway on the corner of Florida Avenue and Twiggs St. (now the Franklin Exchange parking garage), Chip just walked away. “The history is less about the building and more about the Morton Williams grocery store. When I really started going into it, I said to myself, ‘Well this is getting out of my lane.’”

“So when I say I’m not a historian, I mean that I’m not one to the degree of someone like Rodney Kite-Powell who’s just all dug into that stuff,” Weiner added.

Still, for Kite-Powell, there’s one part of Tampa history missing from the book—but it’s no fault of Weiner’s. Kite-Powell explained that at its core, Burgert Brothers was a commercial photography firm. Because of the time in history, their clients were either white or Latin.

“There are definitely some Burgert Brother photographs that do show Black-owned businesses, and they’re incredible, and themselves are so important because there are so few photographs that document Black American history,” Kite-Powell explained. “So if there’s a failing of the Burgerts—and again, it’s not even them, it’s the world that they lived in—it’s that we don’t see the same documentation of Central Avenue, or The Scrub or Dobyville [West Tampa] or other neighborhoods that we do have white and Latin Tampa, but again it’s not Chip’s fault, and I wouldn’t even let that fall at feet of the Burgerts individually, but it’s something where there’s probably a collection out there somewhere. And we’d love to love to see it someday.”

In that sense, Kite-Powell is right. Proportionally to the Black population throughout local history, there just aren’t a lot of surviving Burgert Brothers that capture Black life in Tampa. Yes, there are photos from gatherings at the “Negro Ministerial Alliance” and scenes from classrooms at Blake High, Booker T. Middle School and Darby Elementary, but the Burgert photos are of life inside (Weiner’s book, for its part, doesn’t include photos of people because of the focus on recreating photos of structures past). In fact, one of the few structural photos in HCPLC’s Burgert archives is a 1930 photo from the dedication of the Tampa Negro Hospital on 1615 Lamar Ave. There are people in the photo, which would exclude it from Weiner’s new book, but the organization of the folks—Black guests on the right side of the porch, white ones on the left—speaks volumes about the era the Burgerts were working in.

Weiner’s hope for the book is that maybe in 50 years, someone will pick it up, see what the Burgerts did, what he tried to do and then do it again themselves. But as Tampa gets a chance to celebrate its history with this essential new book, Weiner has also inadvertently opened the door for someone to come in and find what Kite-Powell described as that missing piece. Thanks to this book, maybe that’ll happen sooner than we think.

Support local journalism in these crazy days. Our small but mighty team is working tirelessly to bring you up to the minute news on how Coronavirus is affecting Tampa and surrounding areas. Please consider making a one time or monthly donation to help support our staff. Every little bit helps.

Subscribe to our newsletter and follow @cl_tampabay on Twitter.