Last week marked the first anniversary of a report that Republican National Committee Chairman Reince Priebus commissioned in the aftermath of Mitt Romney’s loss in the 2012 presidential election. It was officially called the Growth and Opportunity Project, but became better known as an “autopsy” of the GOP’s biggest problems. It included just one policy position — support for immigration reform.

“We must embrace and champion comprehensive immigration reform. If we do not, our Party’s appeal will continue to shrink to its core constituencies only,” the report reads. “If Hispanic Americans hear that the GOP doesn’t want them in the United States, they won’t pay attention to the next sentence.”

Consider this Mission Unaccomplished.

Millions of people are affected by the reluctance of the GOP-led House of Representatives to address immigration reform, but the case of Jose Godinez-Samperio is as vivid as any.

On March 7 the Florida Supreme Court ruled that the Tampa immigrant cannot practice law because he’s not a U.S. citizen — but could if the Florida Legislature makes a policy change.

“The Florida Legislature is in the unique position to act on this integral policy question and remedy the inequities that the unfortunate decision of this court will bring to bear,” the justices wrote.

Godinez-Samperio said the ruling disappointed him, but it didn’t come as a complete shock.

Currently working as a paralegal for Gulf Coast Legal Services in Clearwater, the 27-year-old came to America from Mexico at the age of 9 with his parents, who overstayed tourist visas. He learned English, became an Eagle Scout, was valedictorian at Armwood High in Tampa and went to New College in Sarasota. In 2011 he graduated with honors from Florida State University’s law school before passing the bar exam and its moral character test.

The Florida Board of Bar Examiners informed him that it was the first time in its history that an undocumented immigrant had passed the bar. But that landed them in uncharted waters, so they called on the Florida Supreme Court to make an advisory opinion.

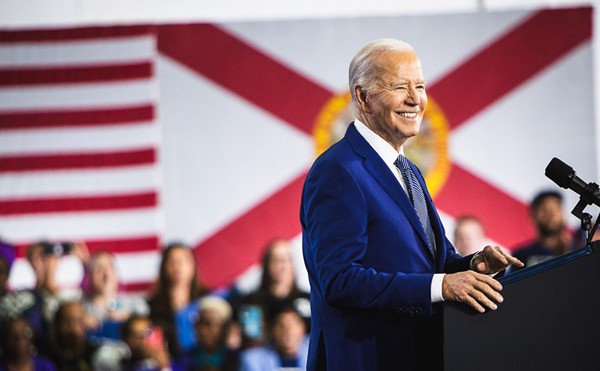

Meanwhile, as his case worked its way through the system, he received a work permit in 2012 as part of President Obama’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, which halted the deportation of immigrants brought to the U.S. as children. A walking symbol of the benefits of immigration reform, he accompanied Tampa area Congresswoman Kathy Castor to the president’s 2013 State of the Union address, and even shared a photo with POTUS himself that evening.

In retrospect, the moment was ironic. Obama’s Justice Department intervened in his case shortly afterwards, filing an amicus brief that cited a 1996 federal law denying specific “state public benefits,” such as a license to practice law, to undocumented immigrants unless a state declares an exception.

“I think that both parties are just pandering for political gain,” Godinez-Samperio says of the White House’s conflicting stance. “It’s very clear to me that all the Democrats want to do is get partisan advantage, and all the Republicans want to do is stall as long as possible. It’s gotten to the point where it’s all about power, not principle.”

A recent letter to the editor of the Tampa Bay Times typifies some of the reaction.

“Why did he not apply for citizenship when he knew that it was a requirement in getting a law license?” Oldsmar resident Marilyn Carlora wrote. “Godinez-Samperio seems to be a perfect case of a person who wants to live and work in the U.S. but does not want to follow the laws.”

Incorrect, he asserts.

“The reason I have not applied for citizenship is because I don’t qualify for citizenship. As a matter of fact, I don’t even qualify for a green card.”

The lack of comprehensive immigration reform is why he’s in a state of limbo. “It’s not like you can just go to the store and buy a citizenship certificate like you can buy a gallon of milk. It doesn’t work like that. [House Speaker] John Boehner needs to step up and change the law. That’s the only way.”

Though all seven justices denied Godinez-Sampiero, Justice Jorge Labarga, an immigrant from Cuba, wrote a separate opinion, in which he compared himself to Godinez-Sampiero.

“When I arrived in the United States from Cuba in 1963, soon after the Cuban Missile Crisis — the height of the Cold War — my parents and I were perceived as defectors from a tyrannical communist regime. Thus, we were received with open arms, our arrival celebrated, and my path to citizenship and the legal profession unimpeded by public policy decisions. Applicant, however, who is perceived to be a defector from poverty, is viewed negatively because his family sought an opportunity for economic prosperity. It is this distinction of perception, a distinction that I cannot justify regarding admission to The Florida Bar, that is at the root of Applicant’s situation.”

“I was very touched by his separate opinion,” Godinez-Samperio says, thinking it unusual for anyone, but especially a Supreme Court Justice, to go out of his way to include something so personal. “Especially an opinion that’s going to be read over and over from many angles and for law schools for decades to come.”

While the Florida Court has put the issue before the Legislature, California’s Supreme Court rejected Holder’s amicus brief and ruled in favor of a man in a similar situation on January 2. That was two months after the California Legislature passed a law that allows the bar to admit “an applicant who is not lawfully present in the U.S. [who] has fulfilled the requirements for admission to practice law.”

The California ruling could allow Godinez-Samperio to obtain a license to practice federal law (like tax law or immigration) anywhere in the country, including Florida. However, it wouldn’t allow him to practice state law in the Sunshine State.

Still, Godinez-Samperio and his team remain optimistic that an amendment could be attached to an existing bill working its way through the House and Senate. Although he says he can’t name any names, they’ve received surprisingly positive feedback from lawmakers they’ve met.

“If that doesn’t happen, we’ll see what comes next.”