Dr. Jarod Roselló's graphic novel, The Well-Dressed Bear Will (Never) Be Found (Publishing Genius Press, 2015), can be a quick, easy read, or a dense, deeply philosophical and political statement, depending on how deep the reader wishes to go.

The back cover issues a warning:

There is a bear loose in the city. He is violent and unpredictable. A menace. If you see this bear, please contact the authorities. Do not approach him, do not call out to him, do not follow him into alleyways or darkened places. Do not go looking for this bear. He is very dangerous. He is also very hard to find.

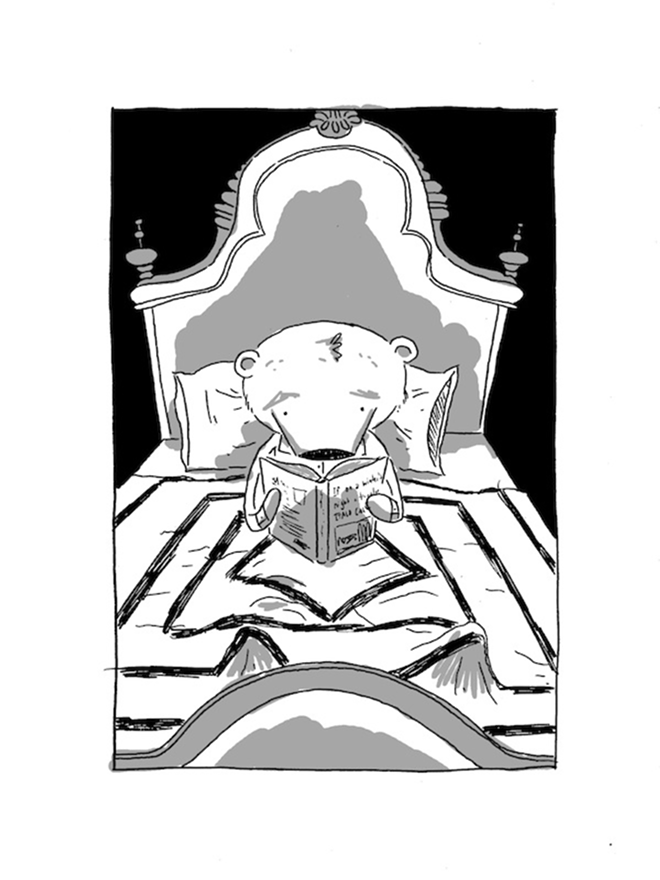

It then opens to the Well-Dressed Bear inside his cozy house, attempting to read Italo Calvino's If On a Winter's Night a Traveler. The Well-Dressed Bear can't settle into his story, however, since the new phone he's just installed won't stop ringing. On the other end of the line, a woman asks for Jonathan. Though the Well-Dressed Bear informs the woman that she has the wrong number, she keeps calling. And calling. And calling.

The only way to escape the ringing is to leave the house, which comes with its own issues. Not wanting to be confused for the dangerous bear on the loose, the Well-Dressed Bear dons a blank but human-like mask. While able to pass, he still feels like an outsider as he walks through his crumbling city. Faceless, hoodie-wearing figures watch him, and, unable to finish his book, the Well-Dressed Bear returns home. When the phone rings again, he has a choice to make: continue asserting that the caller has the wrong number, or pretend to be who the woman on the other end of the line is looking for.

If the reader stops here, The Well-Dressed Bear Will (Never) Be Found is a surreal and often humorous read. Roselló's black and white drawings find a nice balance, offering a clean and simple design with incisive details. It's here, in the details, where the reader can delve further, and in so doing, can begin to see The Well-Dressed Bear... as a commentary on displacement, identity and the ability to pass in a world that champions uniformity and denigrates (or fears) anything different. Certain questions arise: Why, for example, a bear? Why Calvino? These are a few of the questions I was able to ask Dr. Roselló when he took time out of his busy schedule — he's an assistant professor at USF, husband and father of two, and the force behind Those Bears on the online journal Hobart — to answer them.

In a past interview, you said that you came up with the idea for the Well-Dressed Bear during a period of struggling with your Latino identity. Why a bear? What does the bear symbolize for you?

One of the things I really like about working in comics, is that when you draw something it can actually exist. The Well-Dressed Bear is an actual bear, I don't think of him much symbolically or metaphorically. And while he emerged from a particular emotional and psychological space for me, he doesn't necessarily equate to any one aspect. If anything, he's a sort of exquisite corpse, a composite of many things: experiences, sensations, anxieties, memories. That he emerged as a bear is something that seemed to happen outside of my own control. But a bear is a kind of borderland creature: they wander into human territory, they're simultaneously cute and frightening, harmless and dangerous. Bears are one of those animals that humans have a kind of affinity for, while at the same time are cautious or mistrustful of.

The WDB is read as a metaphor for feelings of displacement. Being Cuban, and then living in Miami, Pennsylvania and now Tampa, is that something you've felt in one particular place more than another? In all of those locations? Or is displacement less about a literal, physical location? Do you ever feel displaced as a graphic novelist/cartoonist in the USF CW department?

I think displacement and the feelings associate with it played a big part in making this book. Part of being Cuban-American is feeling historically, geographically, and maybe even linguistically displaced. There's a sense of living in both a physical and temporal exile. I was born in Miami, but this is the anxiety and concern that I inherited from my parents and grandparents. It's learned, for sure, but I think in the future we'll probably find that it's written into our genes as well. That I had just moved out of Miami and was living in Central Pennsylvania only heightened some of those feelings. I found myself grasping around for my identity in a way I never had to do in Miami. I lived in Pennsylvania for seven years and spent much of that time trying to figure out how and where I belonged. Being a cartoonist in a creative writing program, I feel some of that as well. What I do and what I teach is a primarily visual form of art-making. It helps that people who read and write really like comics, find value in the work I do. So while I definitely feel like I'm still trying to figure out how comics works in a creative writing program, I feel welcome in this space.

Speaking of the USF CW department, where you teach the graphic novel, do you teach any other English/writing classes? Do you write other prose or poetry? Which graphic novels do you teach? What can a graphic novel teach compared to a textual novel?

I teach graduate and undergraduate comics and cartooning courses, and I also teach fiction writing courses. I actually started as a fiction writer, and to a degree I still kind of think of myself as a writer who draws. I'm currently wrapping up an illustrated novel, which is as much prose as it is drawing. I tend to teach underground or alternative comics. It's what I'm interested in, what I know, and what I think I'm best qualified to teach. In my spring courses, between the grad and undergrad courses, we'll be reading Theo Ellsworth's Capacity, Simon Moreton's Plans We Made, Eleanor Davis's How to Be Happy, Lynda Barry's What It Is, Sophie Yanow's War of the Streets and Houses, Noelle Stevenson's Nimona, and a few others. The grad course leans a little more experimental and the undergrad course a little more traditional.

What cartoonists/graphic novelists/authors have inspired or influenced you?

Besides some of the ones I listed above, I adore Bill Watterson and Calvin & Hobbes. Early on, Will Eisner's comics, text books and graphic novels were a big inspiration. Lynda Barry has probably been the biggest influence on how I think of myself as a cartoonist and of my craft. And Edward Gorey is probably responsible for getting me excited to tell stories in the first place. I would also list Lydia Davis, Italo Calvino, Reinaldo Arenas, and Paul Auster as some of the writers whose work influences my writing and storytelling the most.

Calvino's Traveler is a book of beginnings/prevented endings. The WDB, because of the ever-ringing telephone, can't finish his book. Is this just a sly little joke or is there a deeper connection?

Ah, Calvino. As I was working on this book, I happened to be reading [Traveler] for the tenth time. It's one of the books I go to when I'm feeling stuck, when I need some motivation and inspiration. Beyond just the idea of interruption, there is, I think a search for truth and meaning found in both texts. We tend to think of language as clarifying and interpretive. That what is written down is true, has authority, and makes sense. The only thing that tends to challenge the authority of text is the primacy of image. In a comic, you have an opportunity to pit language against text, or at least to create tension between the two. In TWDBW(N)BF, the text and the images are telling two different stories, and in the same way the books in IOAWNAT are stitched together, you can either pick them apart, or ask yourself how they might all live together. Calvino was such a tremendous influence on how I thought about the interaction between form and narrative as a young writer, part of it was giving a nod to someone who helped inspire the construction of this text, but part of it was also about adding in yet another text to be read alongside/with/against my own book.

Another thing you mentioned in an interview was that during drawing TWDBW(N)BF you were contemplating what it takes to survive and endure. This ties in with the last question, because, to survive and endure, the WDB does wear a mask when out and about, and in the end he caves and says he is Jonathan to get the phone to stop ringing. So is survival and endurance tied to lying? Appeasing? Hiding?

This is probably getting at the heart of the book, and also at probably the central question that motivates much of what I write and draw. It's hard to make art and not respond in some way to the conditions of oneself and also to the conditions of the world around us. We live in dangerous times, especially if you are black or Latino or Muslim. If you are different or other, the world is a more urgent place, a less certain place. How to live a good life is, I think, a privilege when the world we live in requires so many of us to ask how to live a life that does not end short, that is taken away from us. And for me, people do what they have to do to make it through the day, to make it through the week, the year, whatever it is. The mask, in that sense, is a survival tactic, a way to keep existing.

"Prose writing seeks convergence and comics divergence" is another thing you said in an interview. Have you ever tried to reverse those?

I write and I draw for different reasons. The joy of writing for me is in using language to make sense of something, to interpret, and make meaning, even if those meanings are temporary and qualified. When I draw, though, I tend to disrupt, to break apart, to move outward from experience and into imaginary and impossible spaces. For me, writing is an act of empowerment, and drawing is an act of freedom.

This is the third WDB book, and you have an on-going strip in Hobart. What else is in the WDB's future? And after that, do you have any ideas of what you want to tackle creatively?

The Hobart webcomic, Those Bears, is probably going to be running for a while. I don't know how much of it will appear online before Aaron Burch (Hobart editor) kicks me out, but it's shaping up to be about a 300-page book. I'll probably be working on it for the next couple years. I'm also working on an Edward Gorey-style picture book. It's actually the book The Well-Dressed Bear is writing in Those Bears. The Well-Dressed Bear Will (Never) Be Found also appears in that comic. Together, those three books make up a singular Well-Dressed Bear story. I'm wrapping up an illustrated novel that I think will be out next year, but I can't say anything more about it yet. And I'm slowly chipping away at a pixel art comic that I'm planning to do as a gif comic/novel thing. That's probably enough to keep me busy for a while.

How long does it take to create a volume of the WDB? As a professor, father, husband, creator — how do you find the time? What is your creative schedule/process like?

I write and draw whenever and wherever I can. I keep a couple sketchbooks on me at all times. I draw with my daughter in the afternoons. I sleep very little. I try to prioritize my family and my children's needs, then my classes and my students, and fill every other available moment with writing and drawing. Which is to say, at the moment I have no real schedule. It's guerrilla art-making.

Do you have any advice for people interested in creating their own comic or graphic novel?

Making comics can be the easiest and most arduous thing ever. The cultural space of comics is one that accepts pretty much anything. There's a long tradition of self-publishing, which means anyone can make and publish a comic. When I work with students for the first time, my main goal is to get them to have made a comic all the way through, regardless of what it looks like. Once that first comic is done, then you're a cartoonist, and you're free to make whatever you want.

The Well-Dressed Bear Will (Never) Be Found can be purchased at Publishing Genius Press, $14.95, 210 .